Something interesting happens when you teach something for 25 years. Activities that seem timeless, solid, crowd-pleasers can suddenly feel clunky and old. This semester I had the pleasure and honor of teaching 15 weeks of improv classes to 20 undergraduate students from all different majors at St. Edwards University. I had so much class time with them I could go to my deep cuts and b-sides, playing games I hadn’t led in years. And although much of my go-to curriculum was incredibly effective at helping them live more in the moment, conquer anxiety, tap into their intuitive storytelling abilities and build connections through play, some of it just felt… weird.

For example, practicing different accents–something that was probably my personal portal into performance as a child–now felt icky and gross. For good reason there is now a much bigger emphasis on casting a person of the same background as the role they are playing. Another example was playing with Status in a Chain of Command. I had five players sit in a row and numbered them one through five. Number One was the boss. They only speak to Number Two. They call them Number Two. Number Two calls number one by her title, Ma’am. Number Two is the boss of Number Three and calls them by their number. And so on and so forth down the line. It’s a classic Lazzi– a structured comedic routine that can be improvised within. Number One wants a coffee with cream and no sugar, and this command gets sent down the line. We get to see Numbers Two, Three, and Four quickly switch from being subservient to their boss “Yes Ma’am! Coffee! What a brilliant idea! I’ll have it for you right away Ma’am!” to turning towards their direct report and blustering “Number Three! What are you just sitting there for?? I need some coffee–cream, no sugar–like yesterday! Go!” We get to see on stage in real time what we suspect is happening all the time in our workplaces and families: people being treated poorly then seizing power the moment it’s available to make others suffer. (Side note: when I told my family this story, my kids immediately asked to play the game at the dinner table. And we did with glee.)

But the thing is–these 18-21 year olds were not feeling it. They did not want to be brusk or short with each other. They did not want to even pretend to be mean to each other. I had to increase my coaching more and more–”Say, What could possibly be taking so long Number Two!” Taste the (pretend) coffee and throw it in their face! They looked at me like a lunatic. Like, this is not how we behave.

It was interesting and surprising to me that they seemed so uncomfortable and unfamiliar with a little everyday cruelty. It made me wonder if they really had been brought up on kindness and empathy in a way that was different than the world I was in when I was their age and learned these games and found them delightfully naughty.

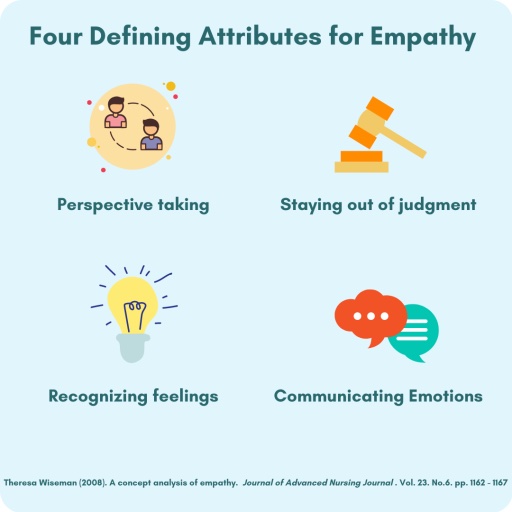

This made me think about the next generation and empathy and Improv. Around the same time of this class I was doing my obligatory middle-aged, white lady viewing of Brene Brown’s recent special on HBO, the Atlas of the Heart, and had to freeze the frame when she introduced Theresa Wiseman’s Attributes of Empathy:

- Perspective Taking

- Staying Out of Judgment

- Recognizing Emotion

- Communicating our Emotion

I thought–I could teach an entire class using this list! I’d call it:

Strengthening Empathy Through Improv. After warmups and introductions, It would look something like this:

Perspective taking: Improvisers thrive on sharing a brain with others and finishing their partners sentences. I would start with a round of Tag Team Monologue. Players line up behind each other single file. Player A, the person in the front of the line, chooses a strong character and begins a monologue as that character. After a moment, Player B who’s right behind them taps them gently on the shoulder signaling Player A to stop talking and rotate to the back of the line. Then Person B continues that monologue as the same character. Players C and D continue in the same way, cycling through the front of the line taking turns creating one character monologue. If they’re doing it well and I had my eyes closed, it would sound like one continuous character monologue. This gives two ways of perspective taking–playing a different character and sharing the perspective of your fellow monologists.

Then I would up the stakes by having two players play a scene, say Player X is a teen sneaking into the house where Parent Y is a parent has been waiting up. And at any moment, I would call freeze and have them swap roles and continue the scene. Now Player Y is the teen apologizing and Player X is the one dishing out the punishments. This switching would continue, more and more rapidly until the scene is complete. Quickly in this exercise, you start seeing the scene not from your point of view or from the characters point of view, but from the author or audience’s point of view. A transcendent moment.

Staying Out of Judgment: I would play a round of movement evolution–like playing telephone with your whole body. It rewards you for seeing everything your partner does as an offer. It helps you let go of seeing things as right/wrong and intentional/accidental. Everything’s just an offer. It increases your full body awareness and acceptance of all you see. There’s a joy in acting as if whatever your partner did was exactly what they were supposed to do and your job is to simply listen and support it.

Recognizing Emotion: there’s a whole trove of theater exercises exploring emotion, but a fun favorite is a game called emotional rollercoaster. Have the group make a list of emotions on the board, often variations on the four base emotions: mad, sad, glad and afrad (to quote Jill Bernard). Have two players start the scene, maybe roommates connecting at the end of the day. Throughout the scene, I’d call out a player’s name and an emotion. That player’s character has to launch into that emotion, physically and vocally express it, and then justify why they are having that feeling in that moment. You’d think these scenes would be all over the place with two characters cycling through 20 different emotions. But they’re not. They are hilariously human.

Communicating Emotion: It’s time to get fancy. I would have two players play a scene, maybe a couple cleaning up after hosting a dinner party. Player A would play the scene without restrictions. Player B could only say “You statements,” often focusing on reflecting the thoughts and feelings they are seeing embodied by Player A. It’s fascinating to watch. Player B becomes incredibly attuned and observant. Player A deepens into their emotions as they are reflected back to them and Yes Anded. I might have them switch assignments halfway through the scene to see how it feels on both sides.

Empathy is a great tool for enhancing connection and compassion. But for some of my students, they are already too hyper-aware of others and their emotional states. These students need to focus on tuning in to themselves and amplifying the voice inside them. Some of Brene Brown’s most fascinating research points to this surprising truth: Those with the most compassion are those with the strongest boundaries. It’s only when we know who we are and what we will and won’t accept that we can truly support others. Once I figure out how to have strong boundaries, I’ll let you know how that workshop goes…

Hi Shana! I love this idea.

I’m curious if you have actually led this Improv and Empathy Class?

I train student hospital chaplains in a program called Clinical Pastoral Education (CPE).

Empathy is a cornerstone of what I teach student chaplains and I often use Brene Brown’s 4-minute animated short on empathy in my teaching.

I’ve seen a strong connection between improv and chaplaincy work. I’ve been incorporating improv games into my curriculum since 2014, and I wrote my Doctor of Ministry dissertation on my use of improv in my CPE curriculum.

I’m wondering if you’d be willing for me to borrow/adapt your empathy curriculum outline for use with my CPE students?

Thanks!

Mark