I’m driving off of Fort Sam Houston in Lieutenant Colonel Mishaw Cuyler’s SUV after finishing my first improv workshop for a military group. I’m wearing my usual black slacks, bright top and high heel Danskos. Lt. Colonel Cuyler is in fatigues: boots, camouflage, the works, just as all his students were. I had just spent a few hours introducing the basics of improv to the soldiers in his class and now Lt. Colonel Cuyler is giving me a mini-lecture in adaptation and military history.

He talks about the early days of World War I, when machine guns were first introduced into warfare. A British Field Marshal named Douglas Haig would have the soldiers still line up side by side in formation and charge against the opposition. Only to get gunned down in scores. Over and over. Until he tallied up two million British casualties under his command.

It’s an extreme example of the life or death consequences of not improvising: refusal to see things as they are, to let go of old ideas, and adapt to the present moment. And it’s ridiculous, almost comical. But it’s real. And something that still goes on today. Old tactics for a new warfare. It’s a clear example of the very real danger of NOT improvising. The consequences of rigidity, turning a blind eye to failures, and being stuck in the past.

This is a big shift from the way I’ve been kicking off my improv classes for the last twenty years, encouraging people to:

1) Have fun

2) Dare to fail

3) Be a good sport

We practice taking a failure bow–celebrating our mistakes as a sign of risk-taking, allowing us to laugh it off and let it go and get back in the moment.

But what’s changed in the past few years is I’ve been delivering this message to new audiences–doctors, college athletes, and soldiers. And sometimes I’m finding my tried and true message falling flat.

Last year, I was in an office building in San Antonio with a panoramic view, doing my “embrace failure” bow to a group of neonatal specialists. One doctor spoke up. “When we mess up, a baby dies. I don’t think we should smile or laugh or cheer about that.”

He caught me off guard and a silence hung for what felt like eons, but was probably half-a-second. I was feeling defensive and scared by his point. Since I’m an improviser, my next instinct was to agree. “Of course not. I’m not recommending that.”

I tried a different tactic. “What happens when we don’t acknowledge our mistakes? What happens when there is a bad outcome and a patient dies and our instinct is to hide it or bury it? What happens to the relationship to the patient’s family and your chances for being sued? What happens to the learnings that could come from that mistake? What happens to the improvements that could result from that mistake? And what happens to you when you are treating the next patient? Or back in the same treatment situation?”

By this point I was back on track to one of my usual mini-lectures about the inevitability of failure and the importance of how you deal with it. How buoyancy is one of the most important factors in long term success. And then we were on to the next game.

But his comment really stuck with me. What exactly was I recommending? What kind of risks and failures are valuable and which do you really want to avoid at all costs? Can taking risks actually make us safer? Is there a time when you don’t want to improvise?

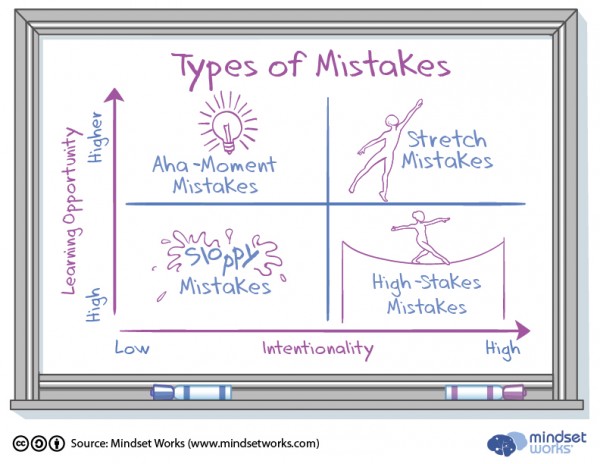

I had an opportunity to explore this when I did a presentation on “Making Friends with Failure” at the UT Athletics department. (Insert your snarky college sports joke here.) Talk about somewhere that doesn’t celebrate losing! These people take their games seriously. So I brought in this chart, about four types of failures.

The Stretch Mistake: This is when you are pushing yourself to do something you haven’t mastered yet. This is the kind of mistake you want to do in practice so you can grow and improve. For example, taking a ton of three pointers at basketball practice to improve your accuracy on game day.

The Sloppy Mistake: This is the mistake of inattention or fatigue. It’s not that informative, except to tell you you need to take better care of yourself or focus more. This is missing your layup that you’ve done a hundred times because you’re not paying attention to too exhausted. Time to take a break.

The High-Stakes Mistake: This is messing up when it counts the most: game day. It could be nerves or inadequate training, but you blow it. You miss your two shots from the foul line that could have tied up the game. These are the mistakes you want to avoid if possible.

The Aha- Moment Mistake: These mistakes are often surprises that lead to discoveries. Maybe you jokingly send a pass to your teammate without looking, and- surprise!–he grabs it and is wide open for an easy shot. Now you have something new in your arsenal that you didn’t think was possible before: the no-look pass.

This gives us some clarity about the kinds of risks I’m encouraging students to take: Stretch Mistakes–trying something new, pushing themselves out of their comfort zones, letting go of planning ahead. They are best done in practice and daily, low consequence situations.

But we don’t want our pilot or our surgeon to try something new, right?

“How about landing the plane a new way today, Steve? It’ll be fun!”

No thank you! When I’m on that plane or under that knife it’s game day and I want protocol followed precisely. The more checkboxes the better.

So, to get more specific, the risks I’m really asking medical professionals or military personnel to take is social and emotional risks. I want them to get used to goofing around with each other and messing up and calling each other on it and owning it. So they feel ready to speak up. To go out on a limb when they see someone not following protocol. To question someone else’s judgement, knowing it won’t be the end of their relationship. To notice when something unexpected happens, instead of going on autopilot. Oftentimes, the disasters happen not when there is a perfect storm of circumstances, but when people who know that something is wrong don’t speak u because they don’t want to damage relationships or go against the rules.

My Medicine Works Co-Presenter Dr. Rob Milman likes to use the example of the Tenerife airline crash. It’s a perfect Swiss cheese line-up of bad circumstances, bad calls, and silent bystanders allowing for the worst plane disaster in 40 years, killing 583 people when two Boeing 747s crashed on the runway at this tiny airport off the coast of Spain. After this disaster, the airlines changed the protocol from having the pilot as king and the crew as his underlings to Crew Resource Management, a more collaborative system where everyone is double checking everyone else, to help avoid this kind of disaster in the future.

And as soon as I think, “I don’t want my pilot to improvise… “I think, “Unless… Unless something unexpected happens.”

If the default plan would lead to a bad ending, I sure as hell want him to abandon that plan immediately and come up with a new one. Just like Captain Chesley B. “Sully” Sullenberger who made an unpowered emergency water landing in the Hudson River after after multiple bird strikes caused both jet engines to fail. That guy improvised and saved 155 lives. He also knew it was the right time to let go of the flight plan and improvise.

That’s an important point I like to make with my groups. Our planning skills are often over-developed, like bulging biceps and our presence and spontaneity skills are like weak triceps. So in my class we are going to work those weak muscles and that might be a little awkward or exhausting, but it will pay off. Because we want to be able to use the right muscle for the right situation. Most of the time planning does the job. But sometimes, in a conversation, a presentation, an emergency, or simply when life doesn’t go as you expect it, it’s time to improvise. And we want to have the strength to handle that moment.

So, I used to soothe my students when they were paralyzed on whether to say “Whoosh” or “Bang” or “Pow” in a game by telling them–it’s not life or death. It’s just a silly little game. But getting good at “Whoosh Bang Pow” and being able to think on your feet and pivot and make decisions and work as a team under changing circumstances–that might just save a life.