Let’s start with a hypothetical.

Your last name is “Merlin.” (That’s not a stage name. Your birth certificate reads “Merlin.”) You happen to love improvising, and you have a knack for it. After studying and performing for years, you decide to strike out and open your own improv school.

What do you call it?

Me? I probably would’ve named it something like “Merlin Improv” or “Merlin’s Improv Magic” or “Merlin Improv.” I’m not good with naming. (See: Mandinka.) But Shana Merlin is good, and so she named her outfit “Merlin Works.” That’s an inspired choice, because it’s a name that … works. It suggests a multitude of interpretations–which is precisely what a good brand name (or tagline) should do. And make no mistake: Merlin Works will own us all someday. And I, for one, welcome our new improv overlords.

SHAZAM!!!

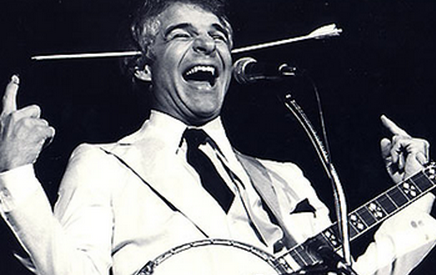

Merlin Works = Steve Martin

I’m talking about Steve Martin as a writer. He’s a comedy legend—on the Mt. Rushmore of Humor, as far as I’m concerned—but to keep with the theme of this five-part series, let’s focus on his published writings. (And not his Twitter account, which is charming, like a hug from a crazy aunt.)

In the summer of 2011 I was feeling shitty and aimless. I decided that signing up for improv classes would, if nothing else, give me something to tether myself to. I needed that tethering. So, I researched all of my options–OPTIONS!!!—online, reading reviews and blurbs and whatnot. I wanted to make an informed choice. Eventually, I picked “Merlin Works” because Shana Merlin had been named “Improv Teacher of the Year” by … someone. Plus, I knew where Salvage Vanguard Theater, where Merlin Works operated, was located.

I signed up, and I went, and I did three levels in a row. (For the record: I didn’t go to Level 4 because there weren’t enough students for the class to “make” back then. Now? It’s a given there’ll be enough, and usually too many.) My abiding love for narrative improv owes much of its genesis to Shana Merlin’s patience and enthusiasm—and from seeing her perform with Shannon McCormick in Get Up—still the most consistently slick duo I’ve personally seen.

I still remember some of the nuggets from those first few classes. “There are really only four emotions in an improv scene: Mad, Sad, Glad, Afra(i)d.” And any decent object work I do is because she made me play with an invisible paper towel tube for an hour.

For me, Steve Martin is an apt comparison because Steve Martin is my earliest memory of laughing at words on a page. My dad, who honed his own comedy and hep cat credentials in the late 60s and early 70s (he starred as Felix in a production of Odd Couple at an Army base near Munich, Germany) gave me a copy of Martin’s Cruel Shoes when I was ten. That book, which is a series of brief comic sketches and essays and short stories, was written the year I was born: 1979. I remember liking that. I remember thinking, “I came into the world the same time this brilliant thing came into the world. That means something.” Of course, at 10, I didn’t really “get” everything in “Cruel Shoes.” But I got much of it, and I knew the parts that were beyond my understanding would come into focus as I grew older. They did. I’ve re-read the book several times since then, and it holds up. Both Martin and Merlin Works were my introduction into a world that would eventually consume me whole: humor, writing, improv.

What I liked most about training at Merlin Works was the atmosphere: an ideal balance of “you can do it!” comfort and “let’s do the next thing!” craftsmanship. This isn’t feel-good therapy, nor is it cut-throat competitiveness. Shana Merlin (and her instructors) know quite a bit about improv—and Shana’s developed a few lessons and insights of her own along the way. So yes, while I felt pushed, I never felt rushed. That’s not an easy mood to accomplish, especially in a classroom of diverse students.

It’s hard to imagine these days, but in the late 70s, Steve Martin was an international superstar. He sold millions of comedy albums. He sold out arenas for his live shows. He was courted by just about every Hollywood studio and TV producer. From about 1977-1980, Steve Martin was untouchable. And why? Because he would do stuff like this:

I kind of think of him as a court jester who’s a thousand times wiser than the king. He’s willing to indulge in his primal silliness and sophisticated wordplay. Puns, old-school jokey jokes, a wild physicality, props, comedy songs, etc. Steve Martin can do it all. And remember, he wrote almost all of his own stand-up material.

But he also wrote The Jerk, which holds up, which will hold up when it’s unearthed by the next sentient race to populate this planet. “I was born a poor black child…”—opening a film that way what’s known in Hollywood parlance as a “balls move.” And sure, his stand-up routine might sometimes seem a bit tame by modern tastes, but his films don’t. Not to me, anyway. The Jerkand L.A. Story (underrated) and Roxanne (underrated). And then, later, as he gets older and bit more contemplative, he produces the delightful novels Shop Girl and An Object of Beauty. All of them funny, all of them touching, all of them whole.

Hell, just go look at all this good stuff.

Merlin Works feels whole. I mean, just check out their website: MerlinWorks.com. It’s gorgeous and chock full of goodies. In the last couple of years, Merlin Works has begun conducting a lot more corporate training. Smart, because that’s where the significant dollars can be found. But just as Martin still plays the banjo—the only part of his oeuvre I’m not a personal fan of— I can’t imagine Shana Merlin would ever stray from Merlin Works’ roots of “teaching folks how to do improv”—and how to do it well.

Because improv works. And Steve Martin is a patron saint. They both helped rescue me.